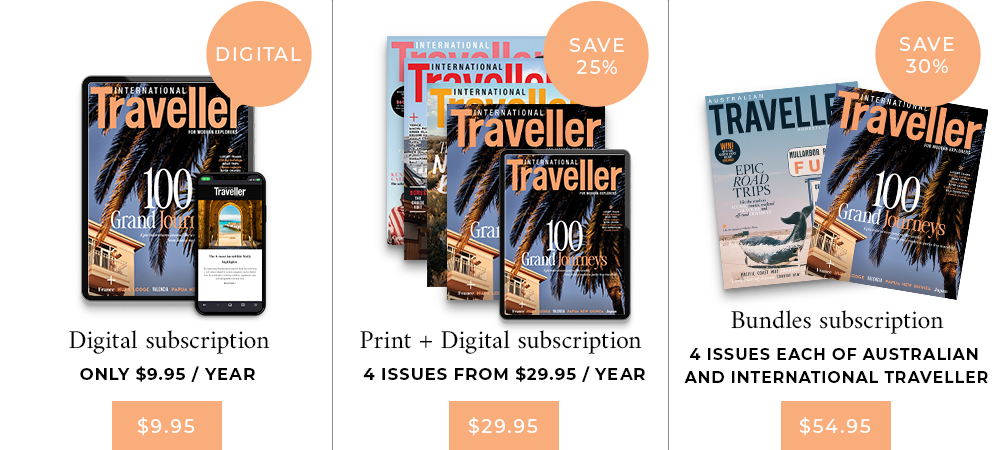

Japan's abandoned spaces are fast becoming its most unique stays

(Image: Tokuto homestay/ supplied)

In Setouchi, Japan’s forgotten buildings may be the most interesting places to stay.

Across rural Japan, abandoned factories, shuttered orphanages, and ageing family homes are being quietly reborn as immersive stays and creative centres. From Kagawa’s sake distillery-turned-gallery to Teshima’s artist residencies, a movement is brewing, transforming humble heritage into habitable art.

Meeting locals in Teshima.

The night I bathed in a rice cooker

We’ve arrived after the rainy dark to this low-slung, shadow-heavy building of glass and time-soothed timber. From the car, I can see inside – hulking outlines of machinery, lazy loops of warm bulbs. It’s moody. ‘Will you be scared in here all by yourself?’ one of my hosts asks me.

Inside, century-old machinery anchors the space to its previous life. (Image: Ivy Carruth)

The noren, that split curtain every Japan traveller knows, announces my arrival as it flaps and flops in the spitting wind. Tonight, I’m sleeping in the master brewer’s quarters of what was, in a former life, a booming sakagura, or sake distillery. From 1877 to 2005, Mitoyotsuru TOJI, in Setouchi’s Kagawa Prefecture, kept the lights on in Mitoyo, one spirited batch at a time.

Part avant-garde art space, part achingly obscure accommodation. (Image: TOJI Mitoyotsuru)

Those days are gone, though. No longer pumping out the proof, TOJI has been recast as achingly hip accommodation and avant-garde exhibition space with the same off-kilter electricity I imagine Warhol chased in his Factory days. Artworks and installations are threaded through the stripped industrial-chic building with intent; certainly not hung politely as mere decor. Think less museum, more “welcome to my curated existence.” There’s nothing here that’s locked behind velvet ropes; step right in.

Off the main entrance of the guesthouse comes the washitsu, or traditional flexible room. (Image: TOJI Mitoyotsuru)

Tucked inside the larger gallery footprint, behind its own entrance, is the sizable residence, which can sleep up to 11 guests. The five entrepreneurs who turned the quarters (once used for workers between gruelling shifts) into luxe lodging wanted not just rooms, but an entire philosophical approach around people “brewing” together.

The Grand Brewing Room includes a Finnish-style sauna, a shallow brew-water bath and the large cauldron. (Image: TOJI Mitoyotsuru)

Thus, the largest space in the residence is the Grand Brewing Bath, with a Finnish-style dry sauna, shallow brew-water pool for lying down, and the elephantine old rice Cauldron, which did its job for over a hundred years. This bath zone could easily fit 20 people, and is just the right amount of metaphor and theatrical flair to represent something more clever than simply adaptive reuse.

The sauna experience follows the nine-step sake-making process – from “polishing” (getting naked) through “steaming” (sweating profusely) to “firing process” (post-sauna drinks and profound conversation) and finally “preservation” or sleep, which is done, very comfortably I might add, on tatami. Although maybe it’s the on-demand sake dispenser that contributes to such sweet slumber? Either way, I get to be both observer and slightly tipsy participant.

An island’s last stand (but make it art)

The food is hyperlocal, and self-sufficiency is a way of life here.

If TOJI represents heritage tourism with benefits, then Teshima offers something more essential: heritage as a survival strategy. This small island in the Seto Inland Sea faces demographic maths that would have an actuary weeping. With just over 700 residents – 70 per cent of whom are over seventy – and six out of 10 of the homes sitting empty, Teshima is essentially betting the farm on art and deeply experiential accommodation to keep its community alive. No pressure, right?

The coastal view outside your window at Homestay Tokuto is the simplest pleasure.

Here’s where I find homestay Tokuto, and where Australians Allan and Reiko renovate abandoned homes into meticulous and spare – yet luxurious – Japanese accommodation. What strikes me most is the honesty of the enterprise. No nostalgia tourism dressed in a vintage kimono, this; it’s a genuine invitation from the community to join their pace of life, for however long the visitor remains. Now that Australians can stay in Japan for up to 90 visa-free days, they’re seeing tourism numbers increase on Teshima, especially since many of us are on our second or third visit to the country. Allan tells me, ‘Travellers are moving beyond Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka, they’re wanting the real deal.’ Intimacy is part of the appeal.

Allan’s from Brisbane; he grew up on the Gold Coast. ‘I consider this the real Japan,’ he reflects. ‘Folks crowd into the big cities to see the cherry blossoms, but there’s a spot not three kay from here where the trees spill with them in season.’ He takes me there. It’s not the right time for that spring bloom of petals, but the grove is densely packed and healthy. We’re the only ones here as the sun lowers. The sky is dressed in Easter egg lavender and pig-belly pink, over a liquid carpet of teal in the distance. It’s clear how much more exceptional this is than being one of the sardines in the bigger cities.

Staying here is about slowing down and seeing the real Japan.

Teshima’s transformation isn’t happening in isolation. It’s part of the broader Setouchi Art island phenomenon, where places like Naoshima have pioneered the marriage of contemporary craft and rural revitalisation. The success of the islands during world-class events like the Setouchi Triennale created a template: take abandoned spaces, add benchmark-setting art and invite people not just to visit, but to inhabit them. What’s evolved is a range of encounters and a Triennale that’s fully subscribed.

But the effort doesn’t stop at hospitality; it extends into commerce and education. Take ShinAiKan, a former orphanage that once protected children in the aftermath of the war. Thanks to the artist collective Usaginingen (rabbit-human), who moved to Teshima from Berlin, it’s now a thriving artists-in-residency program.

Beyond the stay

What links TOJO and Tokuto isn’t their architecture, but their refusal to fossilise. What distinguishes them from boutique hotels is their explicit cultural mission; come, sit down and be one of us, let’s learn from each other. It’s something more existential than just a place to sleep for the night. Japan, in particular, might be a litmus test for this travel shift. The culture is so often consumed via curated tropes that simple everyday life feels radical – not everything is manufactured Instagrammable perfection. Outside the capital cities, it becomes more Japan as process, not Japan as product. The rhythms of daily life and compromises of depopulation, the determined optimism of people who intentionally integrate novelty with local culture; for travellers the privilege isn’t that these places exist, it’s that we’re invited inside. It’s a reminder that travel, at its best, is not simply about consumption. Perhaps it’s stewardship, if only for a few nights at a time.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT